Denmark holds a referendum on dropping EU defence opt-out

Denmark is the greatest EU partner that has a so-called defence uneasiness, but like its Nordic neighbours, Sweden and Finland, it has been reassessing its security policy since Russia began its war on Ukraine.

View polls suggest Danes return closer to European defence relations, and the result could impact their military future.

Equally, there has been an abundance of chaos about what the vote means in a country that is already part of Nato’s defensive association.

Why referendum?

Danish leaders discuss the regional security situation has reversed, and that calls for Denmark to work more closely with the EU on defence matters.

“I believe with all my heart that we have to vote yes,” Prime Minister Mette Frederiksen said during a televised debate on Sunday. “At a time when we need to fight for security in Europe, we need to be more united with our neighbours.”

But for that to happen this traditionally Eurosceptic nation needs a seat at the table.

For 30 years, the defence reservation has meant that Denmark plays no part in most European defence and security initiatives.

“Since it was created until now, generally, it has meant a loss of influence,” said Christine Nissen of the Danish Institute for International Studies. “We are not able to take part in the negotiations. We have no footprint.”

In practical terms, the Danes are not invited to meetings, have little influence and cannot take part in or finance any military operations. The EU is currently involved in several military missions and voting yes could mean taking part in at least two of them, in Bosnia-Herzegovina and off the coast of Somalia. Ultimately the decision would rest with MPs in Denmark’s Folketing.

It would mean joining the EU’s Common Security and Defence Policy, and it would open the door to other security-related agencies. As Ms Frederiksen pointed out on the eve of the vote, Denmark is currently unable to work with its European allies on tackling cyber threats.

The nordic shift in defence policy

Within weeks of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, Denmark embarked on a major policy shift. “Historical times call for historical decisions,” the prime minister said at the time.

A huge boost to defence spending was agreed by parliament in March, with an extra $1bn set aside over the next two years. That would then rise to 2% of GDP by 2033, in line with Nato membership requirements. That was also when the referendum and plans to phase out Russian gas were announced.

The debate in Denmark is all part of a sweeping overhaul of security policy across the Nordic region.

Image source, EPA

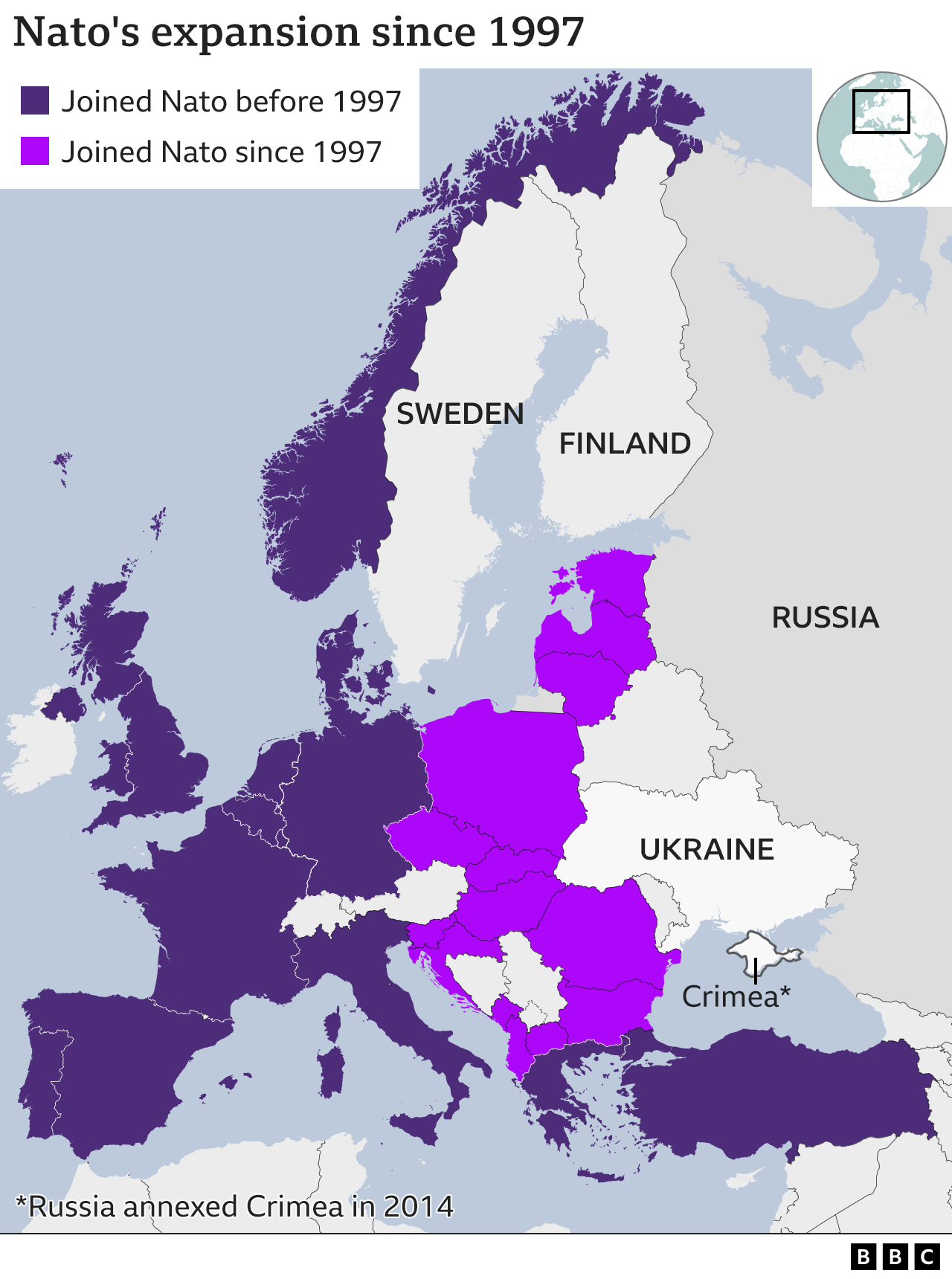

Sweden and Finland have decided to join Nato, ending decades of neutrality.

Denmark is a founding member of the military alliance, but it is currently weighing upon allowing the US or other foreign troops to be stationed on Danish territory.

Copenhagen’s move is understood to have been influenced by a change of course in neighbouring Germany, which has announced a huge hike in military spending.

“I think one should not underestimate the importance of Germany in Danish politics,” said Kristian Soeby Kristensen of Copenhagen University’s Centre for Military Studies. He sees the addition of German money adding considerable weight to the EU’s defence engine.

Latest polls suggest as many as 44% of Danes are in favour of scrapping the defence reservation and 28% are opposed. However, turnout among the eligible 4.3 million voters is expected to be historically low and almost one in five voters are undecided.

“You don’t have to do a large research project to conclude that this is a very sluggish election campaign compared with a local election or a parliamentary election,” election researcher Roger Buch told the Danish newspaper Politiken.

Eleven out of Denmark’s 14 parliamentary parties favour dropping the reservation.

Those against include two right-wing Eurosceptic parties and a left-wing group. Among their concerns are fears that deepening EU defence ties might undermine Denmark’s place in Nato and uncertainty about military involvement.

Why Denmark has been reluctant in the EU

An EU member since 1973, Denmark has often shied away from further integration. And its defence reservation came about after Danes narrowly rejected the 1992 Maastricht Treaty on closer EU integration.

After securing opt-outs on justice, home affairs and the euro, the Danes finally accepted the treaty a year later. While the UK was an EU member state, it also had the right to opt-in or out of several fields including justice and home affairs policies.

According to think-tank Europa, Denmark has used its defence opt-out 235 times over 28 years, but it’s been invoked much more frequently in recent years. This is largely due to Europe’s increasing number of security-related measures, particularly since Russia’s 2014 annexation of Crimea.

Referendums in Denmark on EU-related issues have often ended in a no-vote and this is the ninth so far.

Danes rejected the euro in 2000 and still use the krone. More recently a 2015 referendum on dropping Denmark’s judicial opt-out resulted in a no over worries about losing sovereignty over immigration.

Voting ends at 20:00 (18:00 GMT) and the result is expected before midnight.

Source: BBC