Agencies-Gaza post

Israel killed My Father — Before My Eyes

Even as a child in Gaza I understood that timing is priceless.

That the difference of a second or a minute could determine whether you live or die. Whether you make it home safely or whether you’re killed by the bullet of an Israeli sniper.

In Gaza, our lives are lived by the Israeli military’s timing.

On 18 May 2004, I was in my family home in Tel al-Sultan, part of the city of Rafah close to the sea, nestled in the bosom of my aunt and likely avoiding my mother’s nagging to drink my morning cup of milk.

Though I was only four, I remember impatiently waiting for my father to come home, because he had promised he would return with sweets and hugs for me.

Yet, in these small moments of happiness, Israel found a way to inject its cruelty so that loss would become a lifelong companion.

Only moments later, the Israeli occupation army invaded Tel al-Sultan. It was in these seconds that my future life was determined when an Israeli sniper shot my defenseless father, who had no idea a military invasion was occurring.

The Israeli soldiers let him bleed to death on the ground. They denied the ambulance entry into the area where he was shot and threatened to shoot anyone who moved toward him.

Three of our neighbors were shot and wounded in this way.

A bloody, horrible scene I witnessed firsthand, and one that I haven’t been able to erase since.

My father was wearing baby blue shorts.

Since then, I can’t see that color and not think of it as the color of death.

The Israeli invasion continued until 24 May, killing at least 60 Palestinians. The bodies of many of those killed, including my father’s, had to be stored inside produce and ice-cream freezers) because the occupation army restricted movement.

My fifth birthday fell just seven days after my father was killed.

I remember how everyone around me that day – family members and neighbors – hugged me, patted my hair, and kissed my hands. It was the way they could say sorry for my loss.

My family has wished me health and eternal happiness on every birthday since then. But this has not seemed possible since my birthday celebrations revive the pain of my father’s death.

Last month, I turned 23, and I never thought I would want so badly to go back in time as I do now.

A life without a father

My father’s name is Taiseer Kalloub. I am deliberately using the present tense here as his name lives on despite his death.

Taiseer was born in Bethlehem in August 1975 and came to Gaza as an infant.

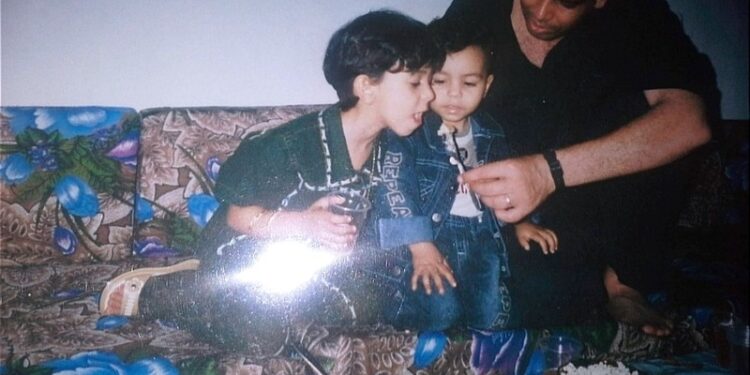

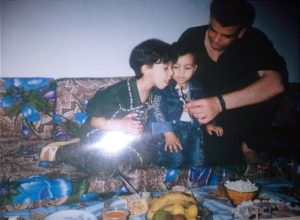

Sahar Taiseer Kalloub (left) with her father (photo courtesy of family).

He had a beautiful voice and would sing night and day. He loved very spicy food and he once carved a map of Palestine from gypsum.

His eyes were green-gray framed with hazel, something inherited by my youngest brother, Ahmed, who was only 4 months when my father was killed.

I remember how my father would give me haircuts, with my family watching on and laughing. He would even give me manicures, taking great care with my little hands.

Eighteen years have passed since my father’s killing, and though one might expect the grief to lessen in time, or for one to come to terms with the tragedy, I have not experienced it as such.

I have never been able to reconcile the brutality of his killing. And to experience, such a loss at a young age only deepens the tragedy.

Quite simply, I want my father back. Nothing can compensate for this loss.

So, I turned 23 this year, and not a brighter version of myself, an individual with enough optimism to carve out a future and live cheerfully. But someone who is father-deprived, with inner wells of psychological devastation.

If I was granted a birthday wish this year, I would wish for my father to come back to life. Because I am not prepared to spend this next birthday without him.

Endless grief

Yearly, I count my lost birthday wishes and I think of one possibility only: what if he were here.

Five months ago, when I graduated with an honors degree in English from the Islamic University of Gaza, I gave a speech to the graduating class. The speech was largely about my father.

Growing up, I didn’t often speak of how I lost my father so young. Pain can live like a secret within us and, sometimes, a loss is so big it can only be handled individually.

Speaking about it requires bravery.

Though I was proud of my accomplishments, of being chosen to give the graduating speech, I wished my father had been there, just as I wished he had been there on my first day of kindergarten to hold my hand.

I felt his absence during those moments and others, like when I yearned to tell him secrets about my first love, my first lie, and my happiness when I made my first orange cake.

We still miss him at our family dinners, how we all bickered over who would get the last piece of mana’eesh.

My father deserved a long life full of happy emotions and occasions.

He deserved to see me, my brothers, and my sisters grow old.

Every time another Palestinian is killed, I turn inward and look for patience, then I count. I count all their family members who will sink nightly in their grief; how many dinners they will miss; how many memories they left behind.

My father should have returned home alive that day in 2004, along with the sweets he had set out to buy.

BY: Sahar Kalloub

Source: The Electronic Intifada