Somalia’s new President, Hassan Sheikh Mohamud, is not new to the job. He served as Somalia’s eighth President from 2012 to 2017 and lost the election in 2017 to the outgoing President Mohamed Abdullahi “Farmajo”.

He made history on Sunday by becoming president in the war-torn Horn of Africa nation for the second time, in the most competitive election in the country’s history, which went into a third round of voting.

Following three decades of conflict, the country remains too dangerous for a one-person, one-vote election, so he was chosen by MPs, who were themselves chosen by clan elders from around the country.

With a background in education, the former peace activist’s election campaign was focused on ensuring Somalis are united and are at peace with the rest of the world – something he did not fail to mention immediately after he was sworn in early on Monday morning.

“I promise you that we will closely work with regional states and our international partners,” he said.

His tone sounded reconciliatory and he promised the Somali people that he would work for everyone.

In the end, he won a huge majority in the third-round ballot, with 214 votes against Mr Farmajo’s 110, gaining revenge against the man who beat him in 2017.

Mr Mohamud spent most of the last two years in Mogadishu, campaigning for the elections to be held on time and as promised.

Image source, EPA

Image source, EPAHe was among the coalition of opposition candidates who were opposed to the attempt by former President Farmajo to extend his term in office by two years.

In February 2021, he came under fire after security forces raided his hotel in Mogadishu to stop protests the opposition candidates were planning in the capital.

He is one of the very few leaders who stayed in Somalia throughout the 30-year civil war.

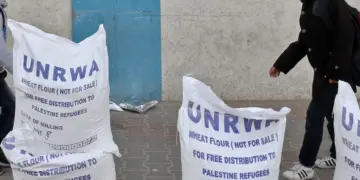

The incoming president inherits a country plagued by multiple challenges, including the continued fight against al-Shabab jihadists who control many areas of the country and a severe drought that the UN is warning could escalate to famine if not addressed. Over 3.5 million people need urgent food aid and are at risk of starvation.

He will also have to tackle the rising cost of living and rampant inflation sparked by the war in Ukraine.

Another challenge he needs to confront is the growing rift between the federal government and regional states, which remained a huge concern throughout his predecessor’s presidency. He is well placed to do this, having created some of those states in his first term.

Rampant corruption unaddressed

Analysts say he will also have to mend relationships with countries such as Kenya, Djibouti and the United Arab Emirates (UAE).

The outgoing administration cut diplomatic ties with Kenya on different occasions and had a dispute over their maritime border.

He has a good diplomatic track record. In 2012, he led the first Somali government to have full diplomatic relations, following previous transitional administrations, and restored ties with both Western and African countries.

But he also faced lots of criticism for failing to address rampant corruption in his administration.

Image source, AFP

Image source, AFPBorn in central Hiran province in 1955, he grew up in a middle-class neighbourhood of Mogadishu and graduated from the Somali National University with a technical engineering degree in 1981.

His contemporaries say he was quiet and unassuming and became a teacher before doing a post-graduate degree at Bhopal University, India.

He joined the Ministry of Education to oversee a teacher-training scheme funded by the UN on his return.

Moderate Islamist

When the central government collapsed in 1991, he joined Unicef as an education officer, travelling around southern and central Somalia, enabling him to see “the magnitude of the collapse in the education sector”.

Three years later, he established one of the first primary schools in Mogadishu since war broke out.

He has links with al-Islah, the Somali branch of the Muslim Brotherhood, which was vital in rebuilding the education system in the wake of the clan conflicts.

It set up many schools with Muslim curriculums similar to those in Sudan and Egypt, but is strongly opposed to jihadist group al-Shabab, which is affiliated to al-Qaeda.

Described as a moderate Islamist in a country which is almost entirely Muslim, Mr Mohamud is also said to have been close to the Union of Islamist Courts (UIC), a grouping of local Islamic courts, initially set up by business people to establish some form of order in the lawless state after years of civil war.

Image source, Getty Images

Image source, Getty ImagesThe UIC brought relative peace to the country in 2006, before Ethiopia invaded and overthrew them – frightened by al-Shabab’s growing influence over the courts.

His followers say he supported any activity aiming to restore peace and stability after.

During the 1990s, Mr Mohamud became very involved in civil society groups. People close to him say he was known for resolving clan disputes.

His first real success on this score was his participation in negotiations in 1997 that oversaw the removal of the infamous “Green Line”, which divided Mogadishu into two sections controlled by rival clan warlords.

Described by some in the early 1990s as the “cancer of Mogadishu”, the division made life difficult for city residents and politicians alike.

In 2001, he joined the Centre for Research and Dialogue as a researcher in post-conflict reconstruction – a body sometimes criticised as being too closely affiliated to the West – and has worked as a consultant to various UN bodies and the transitional government.

His research will no doubt prove very useful as he seeks to help Somalia move beyond three decades of constant war.