How can Ukraine export its harvest to the world?

A new harvest is set to begin, and Ukrainian farmers have 20 million tonnes of grain they can’t transport to international markets. What can be done to provide food to people who are in severe need when global prices rise?

Nadiya Stetsiuk was looking forward to a successful year in early February. In 2021, the weather was nice, and she enjoyed bumper maize, wheat, and sunflower seed harvests on her little farm in Ukraine’s central Cherkasy region.

Because international market prices were high and rising every day, she decided to keep some of her stock and sell it later. Then Russia launched an attack.

Her region hasn’t seen the worst of the fighting – like 80% of the country’s farmland, it’s still under Ukrainian control – but the impact on her farm has been profound.

“Since the invasion, we haven’t been able to sell any grain at all. The price here is now half what it was before the war,” says Mrs Stetsiuk. “There might be a food crisis in Europe and the world but it’s gridlock here because we can’t get this food out.”

Ukrainian Foreign Minister Dmytro Kuleba has described as “blackmail” an offer from Russia to lift its blockade of Ukrainian Black Sea ports, in exchange for the lifting of sanctions.

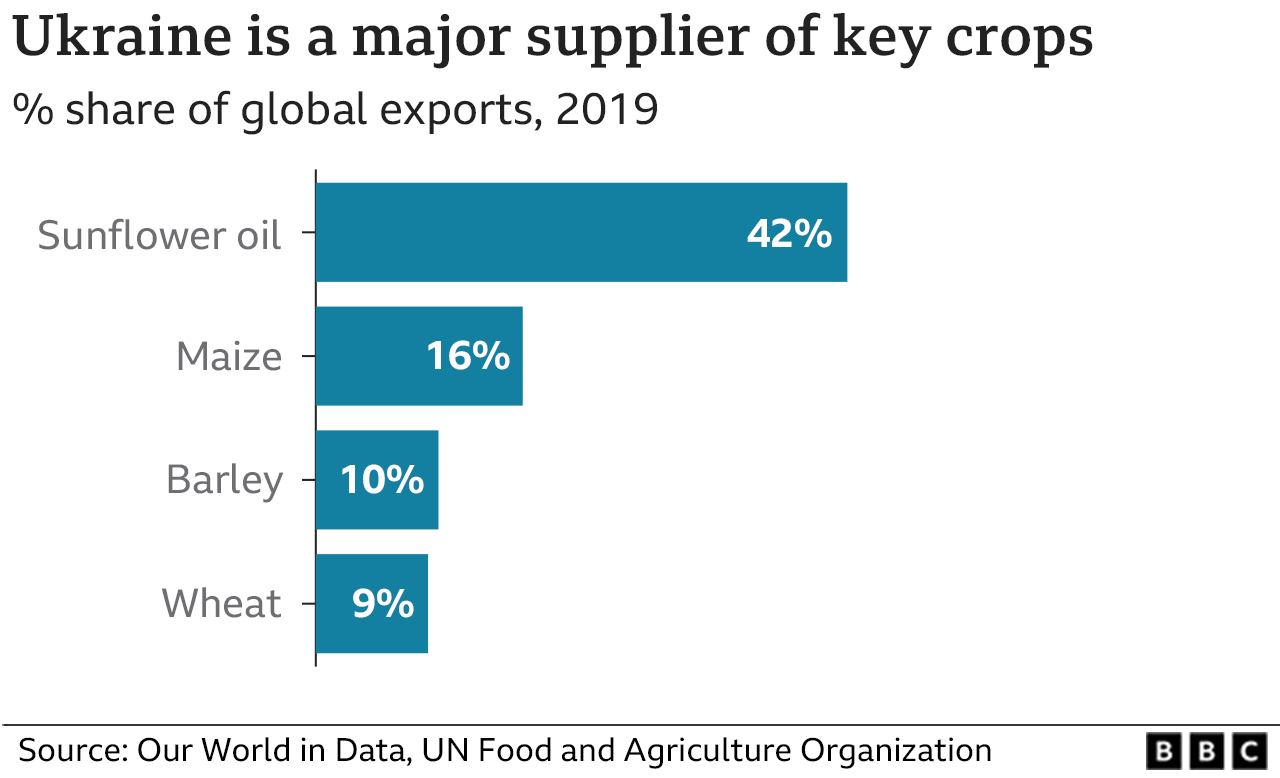

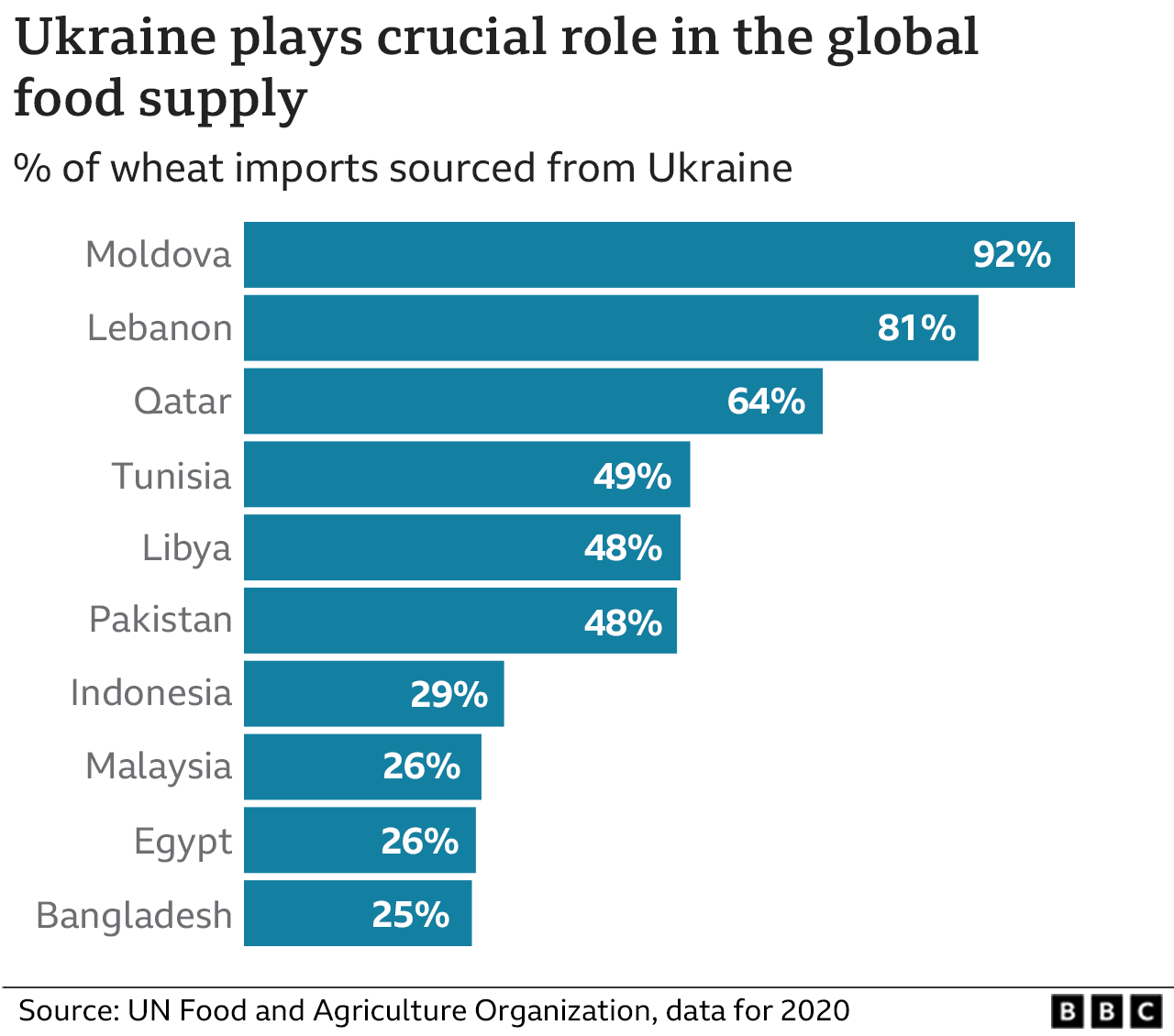

Ukraine punches far above its weight as a food exporter, contributing 42% of the sunflower oil traded on the global market, 16% of the maize and 9% of the wheat.

Some countries depend heavily on it. Lebanon imports 80% of its wheat from Ukraine and India 76% of its sunflower oil.

The UN’s World Food Programme (WFP), which feeds people on the brink of starvation in countries such as Ethiopia, Yemen and Afghanistan, sources 40% of its wheat from the country.

Even before the war, the world’s food supply was precarious. Drought affected wheat and vegetable oil crops in Canada last year, and corn and soybean yields in South America.

Covid had a big impact too. In Indonesia and Malaysia labour shortages meant lower harvests of palm oil, which pushed up vegetable oil prices globally.

At the beginning of this year, the price of many of the world’s staple foods were reaching all-time highs. Many hoped that crops from Ukraine could help make up the global shortfall.

But Russia’s invasion has prevented that. The Ukrainian agriculture ministry says 20 million tonnes of grain are now stuck in the country.

Before the war, 90% of Ukraine’s exports left via deep ports in the Black Sea, which can load tankers large enough to travel long distances – to China or India – and still make a profit. But all are now closed. Russia has seized most of Ukraine’s coastline and blockaded the rest with a fleet of at least 20 vessels, including four submarines.

Image source, Getty Images

Image source, Getty ImagesWFP head David Beasley has called for the international community to organise a convoy to break this blockade.

“Without understanding from Russia, militarily there is so much that could go wrong,” says Jonathan Bentham, maritime defence analyst at the International Institute for Strategic Studies. A convoy would require significant air, land and sea power, he says, and would be politically complicated.

“Ideally to keep tensions low, you’d ask countries on the Black Sea, such as Romania and Bulgaria, to do it. But they probably don’t have the capability. Then you’d have to consider bringing in Nato members outside of the Black Sea.”

That would put Turkey, which controls the straits into the Black Sea, in a difficult position. It has already said it will restrict entry to warships.

Russia’s offer to open a corridor through the Black Sea for food shipments, in return for an easing of sanctions, came as the European Union was discussing on Wednesday a fresh package of sanctions and showed no sign of changing course.

Even if the war ended tomorrow it could take months or years to render the Black Sea safe, Mr Bentham says, as Ukraine has defended its coastline with mines and strategically sunken ships.

Image source, Getty Images

Image source, Getty ImagesFor now, food can only be taken out of Ukraine over land or on barges via the Danube river.

Last week, the EU announced plans to help by investing billions of euros in infrastructure. But Mrs Stetsiuk’s neighbour, Kees Huizinga – who owns and farms 15,000 hectares – says it’s not doing enough.

He’s been trying to transport goods since the start of the war, and is exasperated by the mountain of paperwork the EU requires, which he says has created queues at the border up to 25km (16 miles) long.

“It’s just paper, it’s not like they are actually taking samples of the corn. You just have to have the paper,” he says.

On 18 May, two days after the EU announcement, customs authorities asked his drivers for two forms that they had never seen before. “The border is not getting easier, on the contrary, it’s getting more bureaucratic,” he says.

In the past three weeks, Mr Huizinga has exported 150 tonnes of grain. He could get the same amount through the port of Odesa in a few hours.

“Open the borders,” Mr Huizinga implores the EU, “just let the stuff through.”

Image source, Getty Images

Image source, Getty ImagesThe main route out of the country now is rail. But Ukraine’s rail system is wider than the EU’s, which means loads have to be transferred to new wagons at the border. The average waiting time is 16 days but it can take up to 30.

Though the global conversation around food shortages is largely about wheat, most of the grain leaving Ukraine at the moment is corn. And that is for two reasons, according to Elena Neroba, Ukrainian grain analyst at the brokerage, Maxigrain.

She believes Ukrainian farmers are hesitant to sell wheat because they are haunted by the memory of the Holodomor, a famine created by Stalin in 1932 in which millions of Ukrainians died. Corn, on the other hand, is not as widely eaten in Ukraine.

The other factor, she says is demand. Europe doesn’t buy much Ukrainian wheat, it’s self-sufficient. And it’s difficult to move this wheat on beyond the EU, as ports in Poland and Romania are not equipped to export large volumes of grain.

“By July, EU countries will be busy exporting their own summer harvests and will have even less capacity to handle Ukraine’s food,” Ms Neroba says.

Time is running out to solve the problem. Storage facilities are full and the summer harvest of wheat, barley and rapeseed is weeks away.

Image source, Getty Images

Image source, Getty ImagesMrs Stetsiuk still has about 40% of last year’s harvest stored on her farm and little room for next season’s.

“We don’t want to waste it. We know how important it is for the West, for Africa, for Asia,” she says. “That’s the fruit of our labour and people need it.”

If she can’t sell her stock, she can’t afford to plant this autumn. She hopes the international community can help finance Ukrainian farmers to store grain and to plant again.

If they don’t, she says, grain shortages next year will be even worse.

Many wheat crops are in particularly bad shape right now. In Central Europe, the US, India, Pakistan and North Africa, dry weather means yields are set to be low. In Ukraine by contrast, the weather for wheat has been good.

Mrs Stetsiuk started her farm with her late husband 30 years ago, as Ukraine was emerging from the ashes of the USSR. They were the first in their region to buy farmland and became a proud farming family in the process. Her two daughters and her son are all involved.

“We want to keep doing it. We want to help, providing food to the people.”

In a matter of months, she says, Russia has taken them back at least 20 years.

Source: here